by Simon Makin

A decade ago, clinicians had nothing to offer most people affected by retinal degeneration. Breakthroughs in genetics, bionics and stem-cell therapy are changing that.

Worldwide, 36 million people have total vision loss1. They cannot see shapes or even sources of light. For most of these people, their blindness stems from rectifiable problems such as cataracts — they simply lack access to appropriate health care. The remaining millions, however, are blind as a result of conditions that currently have no effective treatment

Blindness is one of the most life-altering conditions a person could experience,” says William Hauswirth, an ophthalmologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville. As well as the difficulties that it causes for mobility and in finding employment, visual impairment is associated with a host of other health issues, including insomnia, anxiety and depression, and even risk of suicide. “Restoring useful vision would make an almost unimaginable improvement in quality of life,” Hauswirth says.

In high-income countries where preventable causes of visual impairment are routinely addressed, the leading cause of blindness is degeneration of the retina. Found at the back of the eye, this tissue contains specialized cells that react to light and process visual signals, and is therefore crucial to vision. Photoreceptor cells — neurons commonly known as rods and cones — convert light that strikes the retina into electrochemical signals. These signals then filter through a complex network of other neurons, including bipolar cells, amacrine cells and horizontal cells, before reaching neurons known as retinal ganglion cells. The long projections, or axons, of those cells form the optic nerve, along which signals from the retina are carried to the brain’s visual cortex, where they are interpreted as images.

Retinal disorders commonly involve the loss of photoreceptor cells, which depletes the eye’s sensitivity to light. In some retinal disorders, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), this loss results from the failure of the epithelial cells that form a layer at the back of the retina known as the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The RPE keeps photoreceptor cells healthy by cleaning up toxic by-products produced during the reaction with light, as well as by providing nutrients. In retinal disorders in which photoreceptors remain in good shape, the main cause of blindness is degeneration of retinal ganglion cells.

Variety in the causes of visual impairment makes it more difficult to find solutions. But advances in several areas are raising hopes that almost all forms of retinal disorder could become treatable.

One approach is to augment or bypass damaged eyes with functional prostheses. Such bionic eyes can restore only limited vision at present, but researchers continue to push the devices’ capabilities. Another option is gene therapy. Already available to people with specific genetic mutations, researchers are looking to extend this approach to more people and conditions. Some scientists are also pursuing treatments based on a related technique known as optogenetics, which involves genetically altering cells to restore light sensitivity to the retina. This work is at an early stage, but researchers hope that the approach will ultimately be able to help a wide range of people, because it is agnostic to the causes of retinal degeneration. And efforts to replace lost or damaged cells of the retina, either in situ or through cell transplants, hint that even late-stage retinal disorders might eventually become treatable.

Much of this research is in its infancy. But Hauswirth is upbeat about the progress that has already been made. Ten years ago, he says, he often had to tell patients that he could do nothing for them. “For many of these diseases, that’s totally changed.”

Bionic eyes

Almost 30 years ago, Mark Humayun, a biomedical engineer at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, began to electrically stimulate the retinas of people with blindness. Working with colleagues at Second Sight Medical Products, a medical technology firm in Sylmar, California, his experiments showed that such stimulation could induce the visual perception of spots of light called phosphenes. After a decade of work in animals to establish the amount of electrical current that could be applied safely to the eye, and armed with vastly increased knowledge about the number and types of cell that persist in degenerating human retinas, Humayun’s team was ready to begin working with people. Between 2002 and 2004, the researchers implanted a bionic eye in each of six people who had total or almost-total blindness in one eye — the first trial of its kind. Recipients of the device, known as the Argus I, reported being able to perceive phosphenes, directional movement and even shapes2. Around 300 people now experience the world through that device’s successor, the Argus II, which was approved by regulators in Europe in 2011 for use in people with retinitis pigmentosa — a group of rare genetic disorders that cause photoreceptor cells to degenerate. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) followed suit two years later.

To be fitted with an Argus II, patients undergo surgery to attach a chip containing an electrode array to the surface of the retina. To ‘see’ with the device, a miniature video camera mounted on a pair of glasses relays signals to a processing unit that is worn by the recipient. The processor converts the signals into instructions that are transmitted wirelessly to the implanted device. The electrodes then stimulate retinal ganglion cells at the front of the retina. Using the prosthesis is a learning process. Recipients must train their brain to interpret the new type of information being received. And because the video camera does not track the motion of the eye, they must also learn to move their head to direct their gaze.

The device provides only limited vision. Users can detect light sources and objects with high-contrast edges, such as doors or windows, and some can decipher large letters. These limitations arise partly because the device’s 60 electrodes provide very low resolution compared with the millions of photoreceptor cells in a healthy eye. But even this minimal enhancement can improve people’s lives considerably.

Whereas the Argus II is an epiretinal implant — meaning that it lies on the surface of the retina — other devices in development are designed be placed beneath the retina. These subretinal implants can stimulate cells that are closer to those that normally introduce signals to the retina — the photoreceptor cells. By stimulating cells higher up in the visual pathway, researchers hope to preserve more of the signal processing that is performed by a healthy retina.

Retina Implant, a biotechnology company based in Reutlingen, Germany, has built a subretinal implant comprising photodiodes (semi-conductor devices that convert light into electrical current) that directly sense light entering the eye. This eliminates the need for an external video camera, enabling users to direct their gaze naturally. Power is supplied by a hand-held unit, through a coil that is implanted under the skin above the ear. Alpha AMS, the current version of the system, has received regulatory approval in Europe for use in people with retinitis pigmentosa.

Pixium Vision in Paris is testing a photovoltaic subretinal implant called Prima. The system projects signals from a video camera mounted on glasses into the eye using near infrared light, the wavelength of which optimally drives photodiodes in the device to stimulate retinal cells. Projecting images in this way gives users some control over the direction of their gaze, because they can explore the scene by moving just their eyes. Power is also provided by the near infrared light, making the implant wireless and the surgery to fit it less complicated. “Patients are learning how to regain vision faster, and the resolution seems better,” says José-Alain Sahel, an ophthalmologist at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who is conducting safety trials of the device in ten people with AMD. “It’s early days, but this is very promising.”

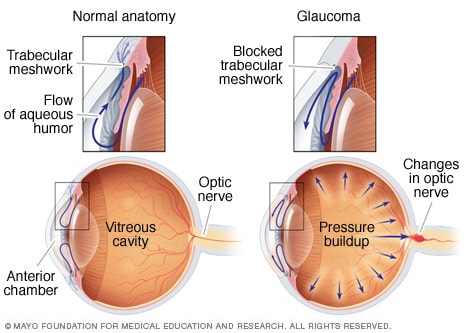

All of these devices work only when functioning cells remain in the retina. In common eye conditions that affect mainly photoreceptor cells, including retinitis pigmentosa and AMD, there are usually some cells left to stimulate. But when too many retinal ganglion cells die, as occurs in advanced diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma, such implants cannot help. For people without any remaining retinal function, whether due to disease or injury, an alternative bionic approach might be more relevant.

Humayun and his colleagues are working on a system that bypasses the eye by sending signals straight to the brain. The idea is not new: in the 1970s, US biomedical engineer William Dobelle showed that directly stimulating the visual cortex triggered the perception of phosphenes3. But bionic-eye technology is only now catching up. Second Sight has developed Orion, a system that is, according to Humayun, “basically a modified Argus II”. Similarly to the original, it uses a video camera and signal processor that communicate wirelessly with an implant, but the chip is placed on the surface of the visual cortex rather than on the retina. The device is being tested in five people with limited or no light perception owing to an eye injury or damage to the retina or optic nerve. “So far, the results are good,” he says. “We’re not surprised by anything yet.”

Given that some of the technology is already tried and tested in people, Humayun is optimistic that the system could receive regulatory approval within a few years. “Obviously, brain surgery has a different level of risk, but the procedure is pretty straightforward, and the Orion could help a lot more patients,” he says. However, much less is known about stimulating the brain to provide useful vision. “We know a lot about the retina but very little about the cortex,” says Botond Roska, a neurobiologist at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel in Switzerland. “But we’ll never know enough if we don’t try,” he says.

Gene therapy

The eye is an ideal target for gene therapy. Because it is relatively self-contained, the viruses that are used to carry genes into the cells of the retina should not be able to travel to other parts of the body. And because the eye is an immunoprivileged site, the immune system is less likely to mount a defence there against such a virus.

In the first demonstration of gene therapy’s potential for tackling blindness, three teams of researchers have used the technique to successfully treat people with Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). This inherited condition leads to severe visual impairment and begins in the first few years of life, often manifesting as night blindness before progressing to broad vision loss that starts at the periphery of the visual field. It affects about 1 in 40,000 babies.

The researchers set out to tackle a specific form of the condition known as LCA 2. This is caused by mutations in RPE65, a gene that is expressed by the RPE. The mutated gene adversely affects RPE function, which in turn damages photoreceptor cells. In 2008, the three teams, including one led by Hauswirth, each showed in early-stage clinical trials that delivering a healthy copy of RPE65 to the retina was safe and led to limited improvements in vision4,5,6. A phase III clinical trial led by Albert Maguire, an ophthalmologist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, showed in August 2017 that people with LCA 2 who received the treatment were better able to navigate obstacle courses at various levels of illumination than those who did not7. In December 2017, the FDA approved the treatment, voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna), making it the first gene therapy for any condition to get the green light for clinical use.

It is possible to treat LCA 2 in this way because the genetic mutations involved show a recessive pattern of inheritance. This means that both of a person’s copies of RPE65 must carry the relevant mutations to cause the disorder. Supplying a single, unmutated version therefore fixes the problem. Conditions that are caused by dominantly inherited mutations, however, require only one mutated copy of a gene to manifest. In most of these, simply adding a normal copy of the gene will not help; instead, the mutated gene must be inactivated. One option is to silence it by adding specific RNA molecules that intercept the mutated gene’s instructions for making the faulty protein, and then supplying a normal copy of the gene to take over its duties — an approach termed suppression and replacement. Another is to correct the mutation using the gene-editing technique CRISPR–Cas9. Researchers at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Modena, Italy, demonstrated this approach in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa8 in 2016. The following year, a team in the United States used it to correct the mutation that causes a type of glaucoma both in mice and in cultured human cells9.

An important driver of gene therapy’s progress has been the use of adeno-associated virus (AAV) to deliver replacement genes to cells. AAVs have been shown to be safe, in part, because they tend not to integrate into their host cell’s genome, which minimises the risk of cells turning cancerous. And their small size enables them to diffuse widely through the eye and therefore infect a large number of cells. But the ability of AAVs to deliver genes has limits: some genes are simply too large for AAVs to carry, including ABCA4, mutations in which can lead to Stargardt disease, an inherited form of macular degeneration. Two workarounds are being pursued. The first uses a virus with a greater carrying capacity, such as a lentivirus, to deliver replacement genes. The safety and efficacy of this approach is unknown but clinical trials are under way. A second strategy is to break the replacement gene in two and transport each half separately into the cell, together with a means of recombining them. “That’s working in at least one animal model right now,” says Hauswirth.

Regardless of the approach, gene therapy has a considerable limitation. More than 250 genes are implicated in blindness, and because each can be affected by numerous types of mutation, the number of potential therapeutic targets is enormous. For example, more than 100 mutations in the gene RHO lead to retinitis pigmentosa, the most common dominantly inherited retinal disorder. Developing a gene therapy for each and every mutation is not practical, says Hauswirth.

Researchers are working on a potential solution that puts a twist on the suppression-and-replacement approach. Instead of targeting copies of RHO containing a specific mutation, they use a silencing RNA to suppress all expression of the gene, whether RHO is mutated or not, while delivering a replacement copy that is immune to the silencing RNA. A team led by Jane Farrar, a geneticist at Trinity College, Dublin, showed the promise of this strategy in 2011 in a mouse model of dominant retinitis pigmentosa10. In 2018, Hauswirth and colleagues tested the approach in dogs with retinitis pigmentosa11. They showed that degeneration of photoreceptor cells in treated areas of the retina could be halted — an improvement that persisted for at least eight months. This strategy tackles all mutations that can cause dominantly inherited retinitis pigmentosa in a single treatment, and therefore extends gene therapy from recessive to dominantly inherited conditions “in a fairly simple way”, Hauswirth says. He plans to study how well dogs that have received the treatment can navigate a maze, and is collecting the safety data required to start a clinical trial.

Optogenetics

Gene therapy works only in people whose blindness is caused by genetic mutation. It is also not appropriate for tackling end-stage retinal disease, in which an insufficient number of cells remain to be repaired. But a related approach based on a technique called optogenetics is disorder agnostic and could lead to treatments for different stages of degeneration. In optogenetics, genes that enable cells to produce light-sensitive proteins known as opsins are delivered by a virus. Introducing opsins can restore some light sensitivity to damaged photoreceptors, or even make other cells of the retina, including bipolar cells or retinal ganglion cells, sensitive to light.

Problematically, however, whereas photoreceptor cells in the eye can cope with a wide range of light intensities — working well in both bright sunlight and twilight — opsins have a limited range and often perform better at high light intensities. A potential solution is to use a set-up that works in a similar way to Pixium Vision’s Prima bionic-eye system, in which recipients are fitted with glasses that incorporate a video camera that captures the user’s view and a projector that points into their eye. As with Prima, the benefit is that the nature of the light that enters the eye can be tailored to the retina’s modification; however, in this case, the intensity and wavelength chosen are those that best drive the newly introduced opsins rather than implanted photodiodes.

GenSight Biologics, a biotechnology company in Paris that counts Sahel and Roska among its founders, is already testing such a system. It aims to deliver an opsin to retinal ganglion cells, but there is a potential snag: retinal ganglion cells are naturally sensitive to light. They express melanopsin, a protein involved in the pupillary light reflex, in which the pupil of the eye constricts in response to bright light. To avoid triggering this, the researchers at GenSight are using an opsin that responds to red wavelengths of light, because melanopsin responds preferentially to light at the blue end of the spectrum. The company began an early-stage clinical trial in October 2018 in people with advanced retinitis pigmentosa who have minimal sight remaining. The trial will involve cohorts from the United Kingdom, France and the United States, and the initial results are expected by the end of 2020.

“This is a simple approach, and we’ll have to see what will be gained,” Roska says. “Then, we can move to more and more sophisticated approaches.” One problem that remains is that many of the disorders that optogenetic techniques might treat involve degeneration of specific parts of the retina, with useful vision being retained in other areas. The light that drives opsins is visible and could interfere with remaining natural vision. In the future, opsins that respond to near infrared light might enable optogenetics treatments to work in tandem with residual natural vision.

Cell regeneration

Stem-cell therapy could potentially cure blindness even in the late stages of disease. Because stem cells can be coaxed into becoming any type of cell, they could be used to grow fresh retinal cells for transplantation into the eye to replace those that have been lost. However, studies in animals have shown that only a small proportion of transplanted neurons are able to integrate correctly into the retina’s complex neural circuitry. This is a considerable obstacle for stem-cell treatments that aim to replace retinal neurons.

The cells that make up the retinal pigment epithelium, on the other hand, sit outside the retina’s circuitry. Stem-cell-based therapies therefore hold most promise for conditions, such as AMD and retinitis pigmentosa, that cause RPE cells to degenerate. “Photoreceptors have to connect to the circuitry but the retinal pigment epithelium does not,” says Roska. “That’s where people are closest to making advances.” Initially, researchers tried injecting the retina with stem-cell-derived RPE cells in suspension, but too few stuck around where they were needed. Several teams now think that a better approach is to transplant RPE cells into the eye as a preformed sheet that is then held in position by a biocompatible scaffold. “The scaffold approach is a huge improvement, compared to suspension, for RPE cells,” says Sahel.

In March 2018, the London Project to Cure Blindness — a collaboration between University College London and Moorfields Eye Hospital in London — announced the findings of a phase I trial in which a sheet of RPE cells was implanted in the retinas of two people with wet AMD (a rare, serious form of AMD involving abnormal growth and leakage of blood vessels). Both recipients tolerated the procedure well and were able to read 21–29 more letters on a reading chart than before the treatment12. The following month, a team led by Humayun reported similar phase I results in five people with dry AMD, the more common form of the condition13. These initial results are full of promise. “This has led to a lot of excitement,” says Humayun. But the findings need to be confirmed by phase III trials in a greater number of participants, and Humayun cautions that the treatment might be many years away from use in the clinic, because no stem-cell therapy for a retinal disorder has yet made it through the approval process.

A related approach, still in the early stages of basic research, could fulfil the hope of replacing lost neurons, opening the door to treatments for a wide variety of eye diseases. In humans, mature neurons do not divide and therefore cannot regenerate, which makes restoring vision especially difficult. But the same is not true of all animals. Reptiles and certain fish can regenerate retinal neurons, and birds also exhibit some regenerative capacity. Thomas Reh, a neuroscientist at the University of Washington in Seattle, is trying to unlock this ability in humans. But rather than transplanting cells grown in the laboratory, Reh aims to coax cells that are already in the retina to differentiate into fresh neurons.

In 2001, Reh suggested that Müller glia — cells that provide structure to the retina and support its function — are the source of new neurons that had been observed in fish and birds14. He and his team then set about finding out whether Müller glia could be used to generate fresh neurons in mice. In 2015, they engineered mice to make Ascl1, a protein that is important for producing neurons in fish, and then damaged the animals’ retinas15. Their hope was that Ascl1 would provoke Müller glia to transform into neurons.

The experiment failed to produce new neurons in adult mice, but succeeded in young mice. Nikolas Jorstad, a biochemist and PhD student in Rehs’ team, proposed that chemical modifications made to chromatin (a complex of DNA, RNA and proteins) in the cell nucleus during development might block access in mature cells to genes that enable Müller glia to transform into neurons. In August 2017, Reh’s team showed that by introducing an enzyme that reverses such modifications, they could coax Müller glia to differentiate16. “For the first time, we could regenerate neurons in the adult mouse,” Reh says. “After all these years I was pretty thrilled.” Although they were not true photoreceptor cells, and looked more like bipolar cells, the neurons connected to the existing circuitry, and were sensitive to light. “I was surprised they connect as well as they do,” says Reh.More from Nature Outlooks

Although far from being ready to treat retinal disorders in people, the work has huge potential. The next step will be to repeat the studies in animals with eyes that are more similar to those of humans. Reh’s team are already working with retinal cell cultures from non-human primates. The researchers also need to work out how to direct the differentiation process to produce specific cell types such as rods and cones. “Now we’ve got our foot in the neuron-making business, cones would be great,” says Reh.

If successful, the approach could be widely applicable. “Ultimately, this will be the way all these eye diseases will be treated,” Reh predicts. “It just makes sense. You don’t have to worry about getting transplants right. Your cells are right where you need them.”

Humayun is also encouraged by the work. “I cheer on anybody with a new good idea,” he says. “It’s very early, it’s high risk, but never say never. That’s what I’ve learned.”

References

- 1.Bourne, R. R. A. et al. Lancet Glob. Health 5, e888–e897 (2017).

- 2.Humayun, M. S. et al. Vision Res. 43, 2573–2581 (2003).

- 3.Dobelle, W. H. & Mladejovsky, M.

Eyeupdate Eye Clinic at 01, Ajuwon junction, Ajuwon bus stoo, Akute/Ajuwon Road, beside BPNL Filling Station, near Lambe Ogun State Tel: 08107531046, 07030000001, 08107531046.

This eye clinic is serving :

alagbole, akute, ajuwon, lambe, matogun, matogbun, giwa, okearo, koye, oke, arifanla, baale, Road, fagba, abule, egba, agege, ogba, ikeja, G. R. A, oshodi, Berger, ojodu, omole, magodo, yaba, mowe, ibafo, shagamu, Ishagah, shomolu, heritage, estate, ajao, College Road, iju, Road, water, works, omole, magado, ketu, ojota, ikoyi, akiode bus stop, grammar school, first gate, Ala Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo, Benin, Edo, Association, Club, Ikorodu, Ketu, Ojota, Shomolu, Cele, Ogun, Lagos, Lagos Island, Lagos mainland, Ifako, Ijaye, eti osa, Oyo, Lisa, Obawole,Iju, Ishagah, Ishaga, Isaga, Isagah, Ishasi,Obawale,Owode, sang ota, abule egba, redeem camp, Ijebu ode, toll gate, bus stop, Street, along, Nigeria

Key words related to eyecare:

Buy,optical, ophthalmic, instruments, hospital, instruments, beds, auto-refractors, keratometer, direct, ophthalmoscope, retinoscopes, optoscopes, lensmeter, slit-lamp, bio microscope, trial, lens, boxes, infrared thermometer, blood pressure monitor, acucheck, phoroptor, phoropter, chair unit, glazing, edging, machine, tonometer, optimal system,colour contact lenses, designer, frames, pupilometer, ventilators,

Gene therapy works only in people whose blindness is caused by genetic mutation. It is also not

Open-angle glaucomaOpen pop-up dialog box

Open-angle glaucomaOpen pop-up dialog box